Coming to a Screen Near You, it's Live from Music Hall

by ANNE ARENSTEIN

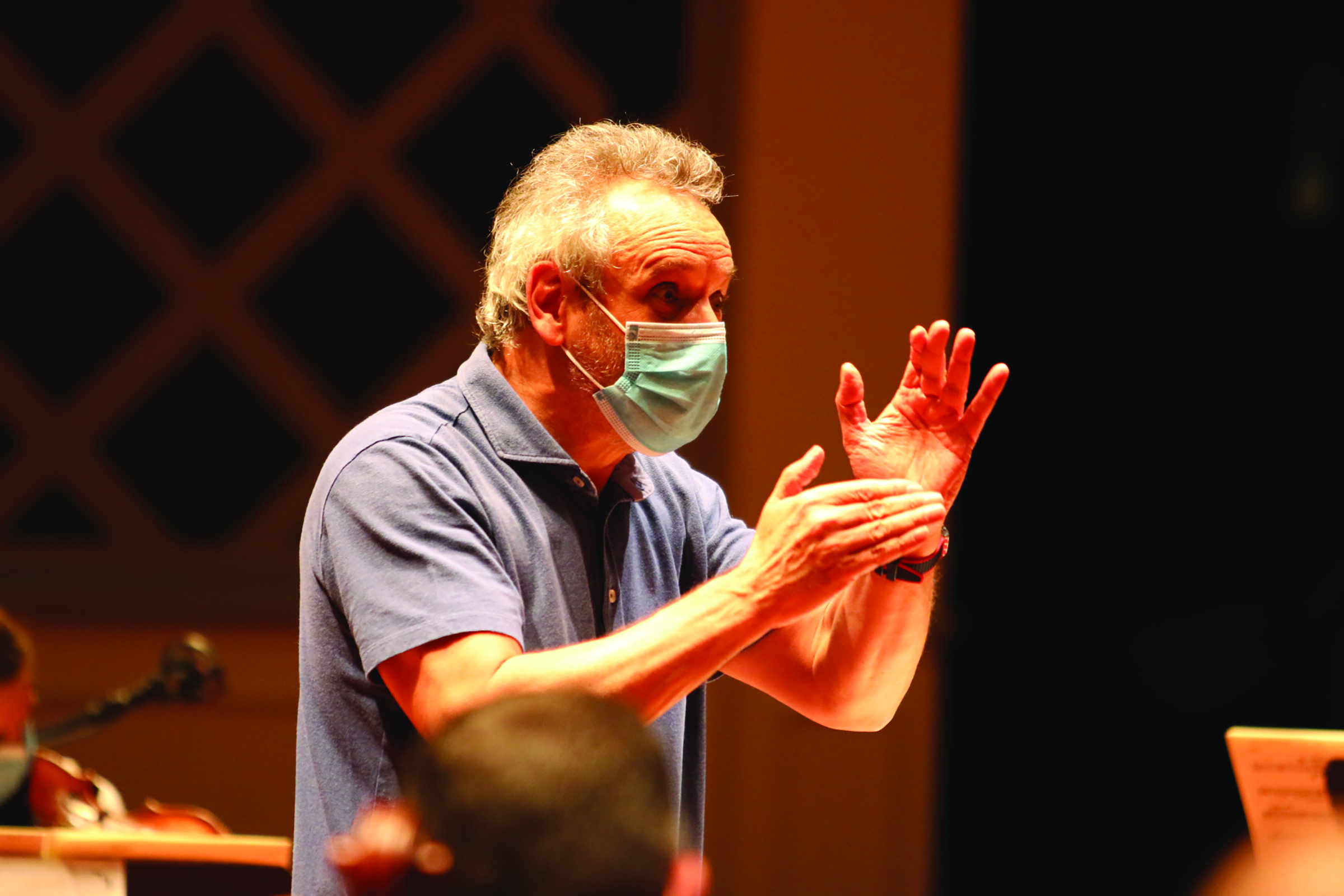

CSO Music Director Louis Langrée and Orchestra members will never forget Friday, March 13, 2020. The final dress rehearsal for the “Handel in Rome” concert with guest conductor Jonathan Cohen was interrupted by an unwelcome announcement.

“The Orchestra was in the midst of the rehearsal when suddenly Paul Pietrowski (the CSO’s personnel manager) came in and told us we had to leave,” Langrée recalls. Ohio Governor Mike DeWine had just signed a mandate closing entertainment and sports venues.

Langrée adds that it was “a necessary decision” given the tragic situation.

For two months, there was no live music in Music Hall, although CSO musicians posted solo performances from their homes. But plans were already in motion for livestreamed small-scale concerts for the CSO and the Pops. Langrée, who is passionate about music’s role in society, readily agreed, as did Cincinnati Pops Conductor John Morris Russell, known as JMR.

“Music is an expression of life for individuals and for society. We cannot remain silent. The May concert came together little by little, with only five musicians, but those were the seeds of making music together,” Langrée says.

The concert on May 16 and the Pops’ July 4th concert provided the CSO with test runs for livestreaming performances. The audience response more than validated the efforts: to date, there have been almost 40,000 views for the CSO concert and almost that many for the Pops.

The logistics of livestreaming are staggering, especially while maintaining physical distance. “In some cases, we’re over-complying,” CSO president and CEO Jonathan Martin explains. “String players are six feet apart and masked, but brass and wind players are ten feet apart and surrounded by plexiglass containment structures that are six feet high.”

For the CSO season-opening livestream, soprano Angel Blue was 22 feet away from the conductor and musicians.

The act of producing a livestream is even more complex—comparable to producing a live TV show. The May 16 performance of Mahler’s Piano Quartet and the world premiere of an oboe fanfare written by CSO creative partner Matthias Pintscher featured six musicians, and the technical crew outnumbered the performers.

According to Martin, there were, at times, camera operators plus robotic cameras, pre-recorded material interspersed with live performance, and lighting changes, as well as directors, camera switchers, score readers, “and a small army of people handling the live stuff.”

“We were really fortunate that almost all the camera crew consisted of the stage crew we work with,” says CSO Concertmaster Stefani Matsuo. “It was nice to see those familiar faces operating the cameras and doing the shots, even with masks on.”

The complexities of livestreaming increase with the number of musicians onstage, which tops off around 45.

Over the summer, the CSO invested in robotic cameras that allow greater flexibility with placement and angles and are controlled from the sound booth at the back of Springer Hall. “We’ve also had more time to rehearse with the cameras and so the quality of images and sound is even better,” Matsuo says.

“I let the director choose what’s best,” says Langrée. “I’m a musician and I make suggestions through the assistant conductors Wilbur Lin and François López-Ferrer, who work directly with the production and technical staff.”

Over the summer the producers were able to experiment with various physically distanced stage configurations and discovered that there were benefits to turning the Orchestra upstage, with musicians facing away from the audience, toward the Central Parkway side of the Hall.

“At first, I wasn’t optimistic, but it actually sounds very good that way!” Langrée laughs. “The world is upside down and we’re playing upside down.”

JMR is equally enthusiastic. “The cool thing is that the cameras look out on the view we have, so people in the audience actually experience what we see. It’s literally the best seat in the house!”

What audiences see on their screens is a digital recording, but Matsuo assures that it’s definitely “as it happened. You’re seeing a live performance, but with the dangers of technical glitches removed.”

The smaller ensemble is only one of the factors that led to a shift in the concert lineup. Accessibility and inclusion are crucial for program planning and viewership. Both Langrée and JMR felt the urgency to address the longstanding social issues of race and inclusion in their program decisions.

“When it comes to programming, you cannot and should not ignore what this country has been going through these past months, so we wanted to present pieces with special meaning,” Langrée says.

“Our first concert was entirely American. We always open the season with ‘The Star- Spangled Banner’ and we had the Catalyst Quartet join the Orchestra for Banner by Jessie.

Montgomery, a Black American composer. Banner intersperses the National Anthem with ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing,’ ‘This Land is Your Land,’ the anthems of Mexico and Puerto Rico, gospel and pop. It’s a statement about this country’s complexities and richness.”

Langrée adds that one positive about pandemic shutdowns and having no concerts for six months has been the time and opportunity he has to read through scores, especially newer works written for small ensembles.

Another of the works that emerged during that increased study time was Anthony Davis’s You Have the Right to Remain Silent (2007), a concerto for clarinet, contra-alto clarinet and Kurzweil effects processor. Langrée especially appreciates what it represents. “It’s a great musical and political piece similar to Beethoven, who always says something bigger than music itself.”

The featured soloist is Anthony McGill, former CSO principal clarinet, now the principal clarinet for the New York Philharmonic and recently named recipient of the Avery Fisher Prize, which rewards not only his captivating artistry, but also his advocacy for social change.

JMR described the process of determining repertoire as an intellectual challenge, anchored by his commitment to acknowledging America’s debt to Black musical influences. “We’re trying to find pieces that speak to everyone,” he says.

The October 3rd Cincinnati Pops program was an extension of the American Originals project that began a decade ago, a story about the formative years of jazz between 1918 and 1950, according to JMR. “So much of this music requires a small orchestra, which we wouldn’t do on a normal Pops concert.”

The program included band arrangements of their own works made by ragtime genius Scott Joplin and jazz innovator James Reese Europe, a new arrangement of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue based on his own two-piano version, and selections from the 1949 breakthrough recording Charlie Parker with Strings. Featured soloists were acclaimed jazz artists Sharel Cassity on alto sax and Aaron Diehl on piano, as well as vocalist Adia Dobbins, who has sung with the Classical Roots Community Mass Choir and has previously soloed with the Pops for Summer Parks concerts and elsewhere.

The fall CSO and Pops livestreams have been offered free of charge, and the CSO maintains that policy throughout the pandemic—a policy Jonathan Martin says is a necessity for audience building and access. “It’s being fiercely debated across the music world, but I believe this is the exact moment when you don’t want to put up pay walls,” Martin says. “We need to provide the opportunity for people who’ve never heard the Orchestra to hear it.”

In addition to online availability, the Orchestra has been presenting watch parties in Washington Park and on Fountain Square, as well as “drive-in” viewings of its concerts at the Starlite Drive-In in Amelia.

Martin acknowledges that, even when performances resume in Music Hall, livestreaming will be an important part of the CSO’s and Pops’ outreach and engagement efforts. But for now, it’s a lifeline for audiences and performers.

“Doing these livestreams is such a privilege for us. All of the musicians are so grateful to play together and to be communicating with our audiences,” says Matsuo.

“I’m super excited to work with Anthony McGill and for the Davis piece, which will be a first for me,” she adds. “I’m also really excited for Augustin Hadelich to play Chevalier Saint-Georges' Violin Concerto—Hadelich is such a world-class musician. And Angel Blue, her voice is so incredible…. The fact that we’re still able to have these artists come is amazing.”

“We can’t wait to see audiences again in person. It will be so nice,” she adds wistfully.

JMR says that the energy lacking from a live audience is made up for by a great team of musicians, as well as administrative and technical staff.

“The support, the love, the appreciation that everyone brings to work has been awesome. To me, it’s the hallmark of an exceptional organization.”

Langrée hopes that the livestreams will help audiences to gain a sense of community, and he says that the pandemic underscores his belief in the orchestra as a metaphor for society-at-large.

“People are now talking to each other loudly and not listening enough. If you do that as a musician, it’s just mission impossible. There’s no blending, no phrasing, no sense of unity.”

“Music should help us to feel united,” he concludes. “It’s essential, addressing the sensibility of people, and helping each of us to rise to our best.”