Under One Roof: The African American

Experience in Music Hall

by Tyler M. Secor

For many years, Friends of Music Hall (FOMH) Board Member Thea Tjepkema has been digging through newspapers, program books, archives, historical documents and account ledgers, and talking with historians and Cincinnatians to reconstruct the various histories of Music Hall. Her curiosity and diligent research of all things Music Hall prompted the FOMH to name her Archivist and Historian this fall. One of the untold narratives Tjepkema continues to uncover is the African American history of Music Hall.

Tjepkema says the catalyst for this project was (her husband) John Morris Russell’s quest for information as he was working to program the CSO’s first Classical Roots concert following the Music Hall renovation. “John wanted to understand the African American performers, athletes and public figures who appeared at and had an impact on the Hall’s history. As I researched, I started uncovering the inspiring—and often painful—nearly 150 years of undocumented history of the African American experience in Music Hall, which opened a new dialogue about what this building means to Cincinnati.”

Fountain Lewis, The Cincinnati Enquirer, April 11, 1897

This story, however, doesn’t begin with the bright lights on the Music Hall stage; instead, it starts with a donor list and a haircut.

In 1875 Reuben Springer gave the initial $125,000 donation to kick-start the fund to build Music Hall with the stipulation that the same amount would be donated by the community. At the grand opening of Music Hall on May 14, 1878, Julius Dexter, chairman of the building committee, spoke to the 6,000-person crowd squeezed into the 4,428-seat auditorium about the gift that Springer made, saying, “It is not the amount of the gift which especially entitles him to our gratitude. Other persons may have given as much, possibly, in proportion to their means more. Who may say that the contribution of the colored barber, or the hard-working mechanic of a rolling mill, is not the equal in liberality with any thousand dollars, or even with the largest sum given?”

Tjepkema scoured the papers and the Cincinnati Music Hall Association’s 1877 annual report of donors looking for the name of this African American barber. Ultimately, she found not only his name, but a remarkable story of altruism and dedication to family, community, and church in Fountain Lewis. An entrepreneur for over 50 years, Lewis established his shop on Fourth Street, where he was the barber for prominent Cincinnati men. In an 1897 Cincinnati Enquirer story, Lewis was quoted as saying, “Grand and magnificent men were customers of mine at that same old shop. There was Reuben R. Springer—and he got me to be one of the subscribers in the fund to build the Music Hall, and you can depend on it I’m mighty proud of the fact now.”

Sissieretta Jones, 1899, Metropolitan Printing Co.,

Library of Congress

Hopefully, Mr. Lewis was in the audience March 10–12, 1893, to hear the first African American soloist perform on the stage of Music Hall. Fresh from a performance in Carnegie Hall, Sissieretta Jones made her Cincinnati debut at a Friday matinee to an audience the Enquirer described as the “best element of white and colored citizens,” in their review. Mme. Jones performed arias from Bellini’s Norma, Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine, and her popular ovation Comin’ thro’ the Rye. The crowd and critics loved her, declaring her performance as the best given in Cincinnati in some time.

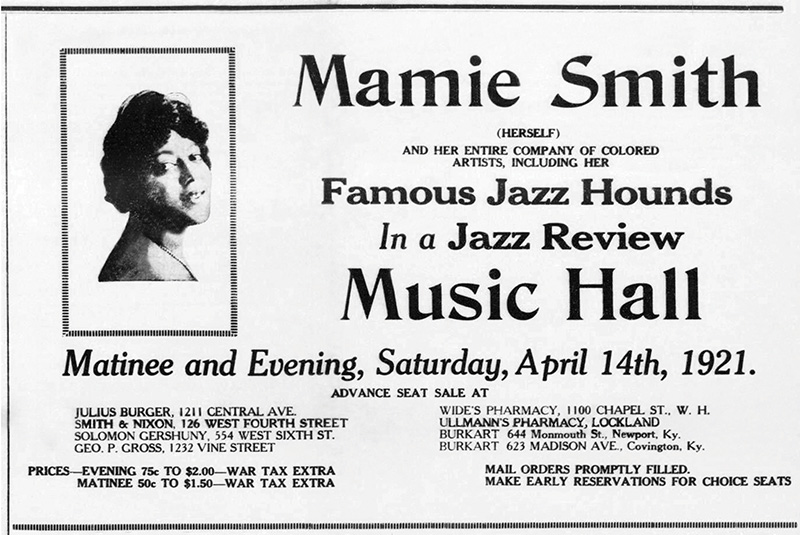

The “Queen of the Blues,” Mamie Smith, born eight blocks south of Music Hall, was the headliner on April 16, 1921, kicking open the door to the Jazz Age on the Springer Auditorium stage.

Seven years later, the Greystone opened as America’s largest ballroom with room for 5,000 dancers on the second floor of the South Hall of Music Hall (the current Music Hall Ballroom) presenting a veritable “who’s who” of prominent African American jazz artists.

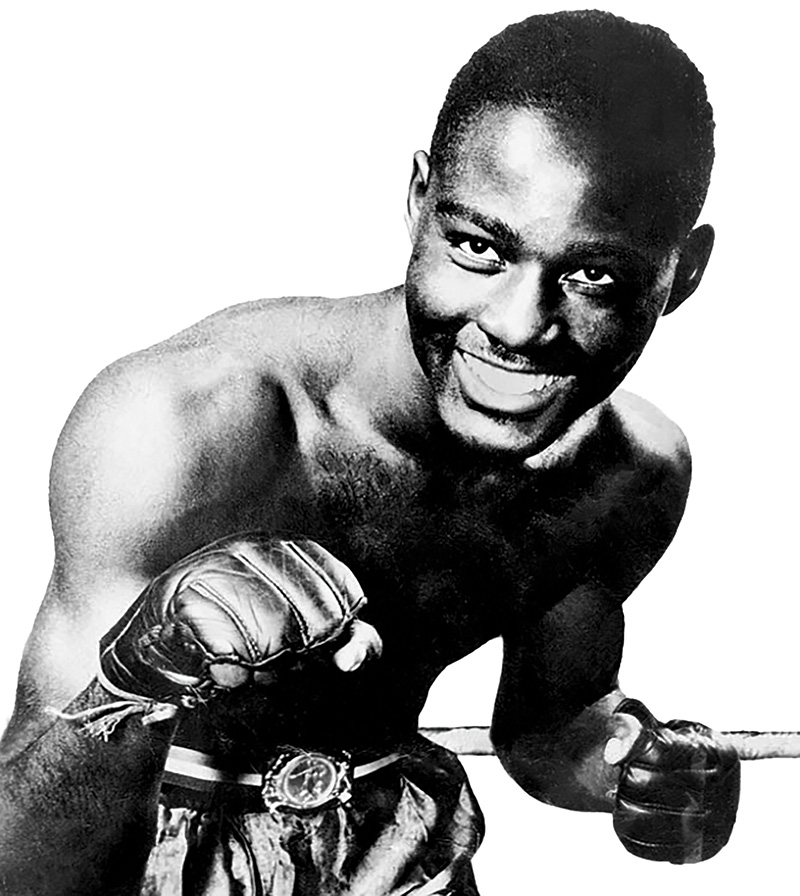

Ezzard Charles, reemusboxing.com

On the same day, a 6,000-seat sports arena opened in the North Hall of Music Hall, where for the next 30–40 years prominent amateur and professional Black boxers were literally fighting to break down the color barrier. One of those boxers was World Champion, “Cincinnati Cobra,” Ezzard Charles, who began his amateur and professional career in the North Hall.

“Piecing together these stories laid bare many uncomfortable truths that are part of our city’s history,” says Tjepkema, “but at the same time revealed a world of music and artistry within Music Hall that must be brought to light and celebrated.”

Tjepkema has collected many more stories of the African American experience in the three buildings that are under the one roof of Music Hall. To learn more of this fascinating history, the Friends of Music Hall offers in-depth blog posts, and Under One Roof: The African American Experience in Music Hall, one of several presentations offered through their Speakers Series. Visit friendsofmusichall.org for more information.