How a pandemic, Fibonacci, and a desert landscape influenced Adams’ Variations

One of the many ironies of Samuel Adams’s Variations—a piece, incidentally, devoid of any classical “theme and variation” formula—was that it had been written at the behest of Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, where Adams had been appointed composer-in-residence in 2020. As a result of the Covid pandemic, Adams was “in residence” neither in the Netherlands nor his longtime home in the Bay Area, but rather (as he describes it) in “desert suburbia.”

“Once it became clear that my wife wouldn’t be working for a while—she was a violinist with the San Francisco Symphony—we left for western Nevada,” he says. “I like to say that composers are social distancers by profession, but for about a year and a half we were literally out there by ourselves.”

Well, not entirely by themselves—there were the Canada geese—but the pared-down environment soon took root in his music. “The desert was so unbelievably gorgeous. And for seven or eight months, I was basically stationary and became very sensitized to gradual changes in my surroundings,” he explains. “So these ‘variations’ are really a series of gradually, almost intangibly, morphing environments. Certain themes and core harmonic ideas reemerge as the piece goes on, but the sense of ‘variation’ has much more to do with kaleidoscopic changes of color and energy.”

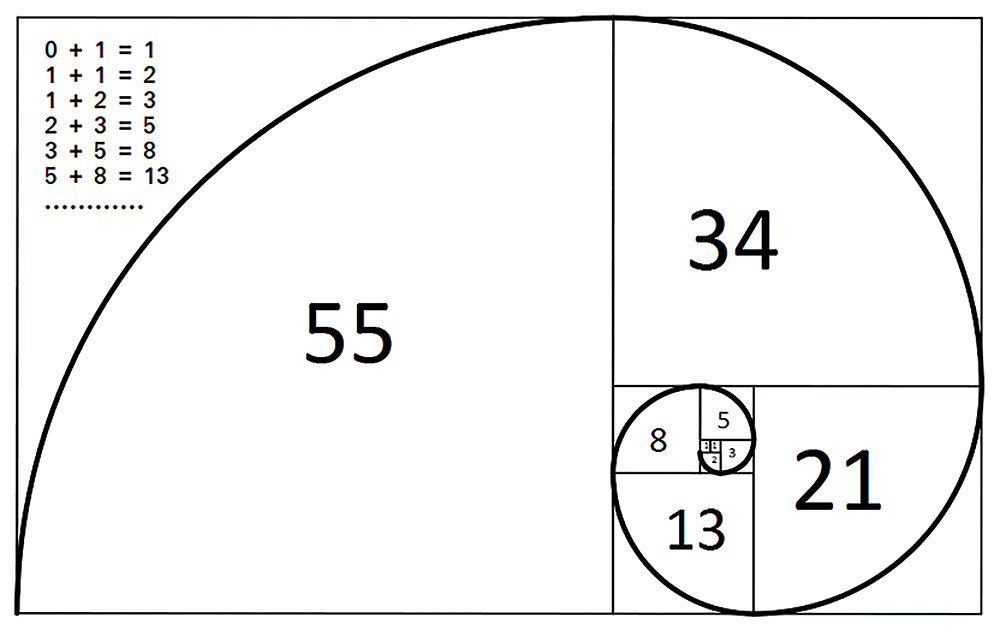

Structurally, the six sections expand exponentially—from one minute to two, then three, then five, then eight—mathematically following the Fibonacci sequence but also intuitively reflecting both the expansive nature of the pandemic lockdown and the gradual reopening of space that offered new possibilities.

“This piece, which I started in June 2020 and finished in January 2021, marked the beginning of a whole new chapter where I began reconsidering my priorities as a person and a musician,” explains Adams, who has since relocated with his wife and newborn child to Seattle. The piece’s belated world premiere—the 2021 performance originally set for Amsterdam has been rescheduled for 2024—follows on the heels of his “non-concerto” No Such Spring for piano and orchestra (scheduled for its world premiere in February 2023 with pianist Conor Hanick and the San Francisco Symphony), which he says is an extension of the same sound world.

“I think the change in my music mirrored the change in my emotional state,” he says. “I used to expect audiences to lean in, probably more than they were comfortable with…. Now I feel it’s important to create a sense of immediacy. When I was in my 20s, I used to think that complicated music was by definition complex, but I’ve learned that those are very different things. Mozart is simple, but complex. And a lot of complicated modernism is actually very facile. Now, I’m trying to write complex music, but with many points of entry so that a wide range of people—with their own individual listening histories and variety of personal experiences—can find their way in.”

Read the CSO Cover Story "Premieres, Mermaids and Deafness: Bringing New Works to Music Hall."