Revisiting Old Landmarks and Making New Discoveries

by Ken Smith

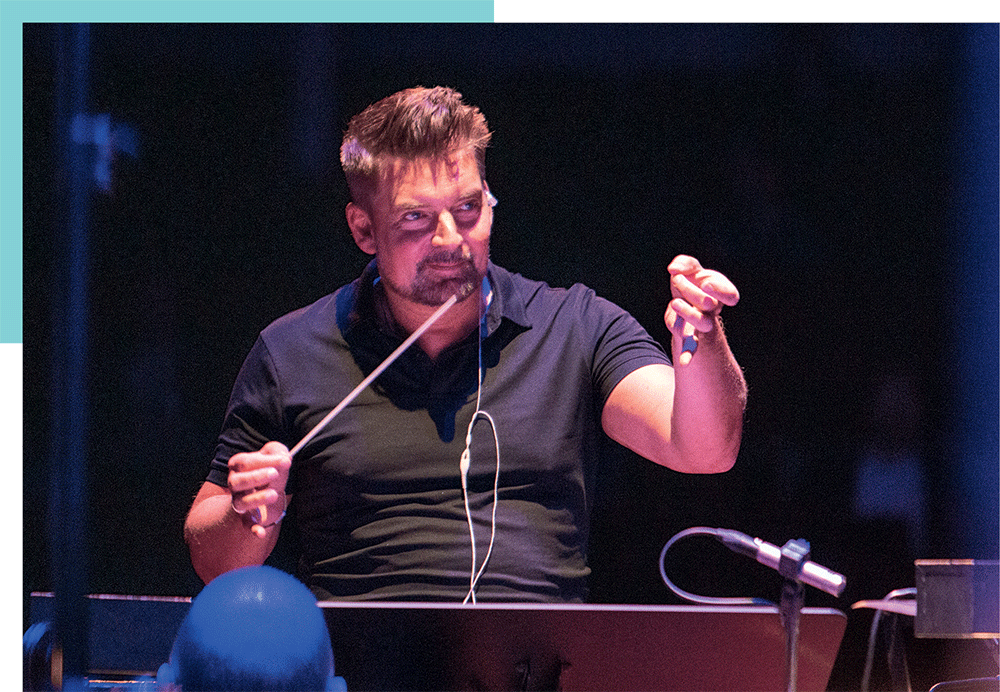

For Louis Langrée…the commute between Paris and the

United States still yields new discoveries,

especially when passing the

old landmarks from different directions.

Those who shuttle back and forth from one point to another often find it rewarding to vary the route. For Louis Langrée, who ends his tenure as Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra Music Director next season, the commute between Paris and the United States still yields new discoveries, especially when passing the old landmarks from different directions.

Saint-Saëns’ Symphony No. 3, last performed in Music Hall before the renovation, became a cornerstone of the CSO’s 2017 Asian tour. “We may hear the piece a lot on the radio, but it doesn’t get performed very often in the concert hall,” Langrée laments. Much of the reason, he says, is due to the bulky solo instrument of its subtitle: the organ. The distinctive sonorities bring to mind a church service in the middle of a secular gathering.

“The 19th century was full of composers asking, how is it possible to write a symphony after Beethoven’s Ninth?” he explains. “Berlioz went the narrative route with Symphonie fantastique. Franck and Bruckner went into ritual-like, almost liturgical celebration. Saint-Saëns took the more ambiguous direction of mixing the two. Is his Organ Symphony a Mass or a concert? To be honest, the truly great symphonies blur such distinctions. They all start with their version of a Kyrie, full of anxiety and doubt, and little by little arrive at full light by the end.”

So when the Organ Symphony returns to Music Hall May 5–7, the obvious question is what else do you put on the program? “At some point, Saint-Saëns distorts the Dies Irae to the point of caricature, almost like a gargoyle.” Langrée says. The first thing to cross his mind was Symphonie fantastique, which similarly tweaks the same melodic theme. That piece was too long, but, fortunately, Berlioz’s Overture to Les francs-juges (“The Judges of the Secret Court”)—his rarely performed first orchestra piece from a discarded opera—was just the right length.

“You don’t need to know the story,” Langrée says, “you can feel the terror and rage and aggression in the music. You hear the music that later became the Scaffold March in the Symphonie. Berlioz at this age had no technique, so he was forced to invent new ways to say everything. It’s quite weird, and you can either say, ‘Oh, that’s weird…whatever,’ or ‘Oh, that’s weird…how extraordinary!’ because you can already see the seeds of the genius.”

Much of Saint-Saëns’ charm lies in the range of expression, and to accentuate his music’s delicate side, Langrée veers in the opposite direction with Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major, performed by soloist Víkingur Ólafsson. “Countering Berlioz, whose musical world is big and savage and cruel, we have the super-sophisticated Ravel, whose concerto is really more like chamber music,” Langrée explains. “Saint-Saëns had dedicated his Organ Symphony to Franz Liszt, the archetypical womanizing priest, so you can see how already there were really two worlds being evoked here. And Ravel himself said that in writing his concerto he was thinking about two composers, Mozart and Saint-Saëns, so it all comes together and makes perfect sense.”

By contrast, no such question of musical pairing entered the mind of CSO Creative Partner Matthias Pintscher, who will be conducting only one piece on his April 21 and 22 program: Mahler’s Symphony No. 7. “I have a very particular vision of how to present Mahler’s Seventh, one that wouldn’t be appropriate with any of his other symphonies,” says Pintscher, who is returning to the piece for the seventh time in the past decade. “There’s an eminent, omnipresent orchestral structure, but it often strives and longs for a more transparent chamber-music aspect. I believe it really foreshadows not just what happens in his Das Lied von der Erde [“The Song of the Earth”] but also the works of Anton Webern.”

Performing Mahler’s 80-minute symphony as a stand-alone piece was not Pintscher’s initial impulse. Rather, that decision came after his search for a companion piece yielded no curtain-raisers that seemed suitable in proportion. “It’s actually become my dream to commission a composer to write a third Nachtmusik [“Night Music”] that relates to Mahler’s music and insert it somewhere in the Seventh Symphony,” he says. “Is that almost sacrilege? Maybe, but since we’re all talking these days about reinventing the concert format, maybe not.”

To bring the current season to a close, Langrée has fashioned a program for May 12 and 13 that could be named not just for one of its works—An American in Paris—but also its inverse. “I wanted to finish the season with both American music and French music influenced by Americans,” he says. His “Frenchman in America” portion opens with Darius Milhaud’s La création du monde (“The Creation of the World”), which Langrée calls “the first jazz homage” in the concert world.

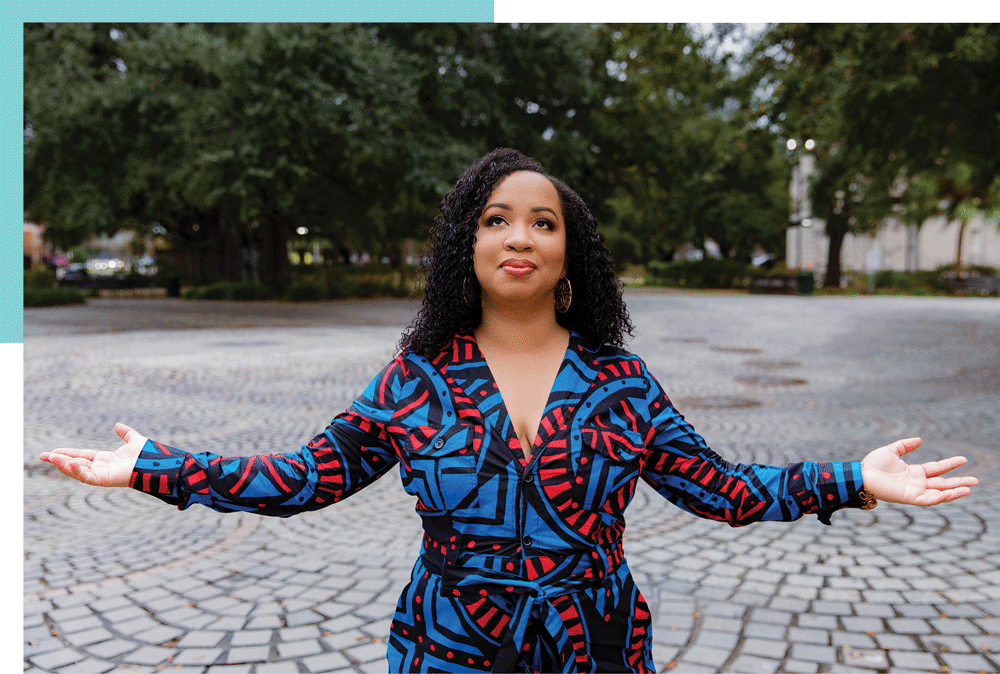

The main event of the evening is the world premiere of Courtney Bryan’s Piano Concerto, House of Pianos, with the composer herself at the keyboard. Bryan, a jazz pianist and composer whose music draws heavily on jazz and gospel traditions, grew up in New Orleans, where her earliest musical memories came from the church.

“My church was Saint Luke’s Episcopal,” she recalls, “an Anglican church where the people were mostly Caribbean and some West African. And this cultural mix was reflected in the music. Along with really traditional English hymns and Gregorian chant, we’d have spirituals and occasionally some African drumming and different Caribbean rhythms. And I got very used to this.”

Studying piano from age five, Bryan found that her teachers not only indulged her penchant for “making things up” at the keyboard, but also taught her how to write them down. “My teacher also told me to start using the word ‘compose,’ which meant that, even though it was fun, it was something to take seriously.”

Bryan’s sense of musical collaboration grew steadily, from her high school days at the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts, where she first started writing music for other instruments than the piano, to her undergraduate years at Oberlin, where she had access to dancers and a much broader range of collaborative artists. She furthered her music education at Rutgers and Columbia universities, where her advisor was the composer and trombonist George Lewis.

Bryan’s efforts at performing and writing music for others, after years of following roughly parallel tracks, finally converged again on a bigger scale. Finding herself in separate discussions with the CSO and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Bryan negotiated a co-commission for a piano concerto with a chamber-sized orchestration for Los Angeles and a full orchestration for Cincinnati.

With a loose deadline and plenty of time to contemplate the commission during the pandemic lockdown, Bryan decided to turn the piece into a tribute to the pianists who shaped her musical life, starting with Scott Joplin and Frederick Chopin and continuing through stride players like James P. Johnson, Fats Waller and Jelly Roll Morton, whose music she played less frequently. On the classical side there was Sergei Rachmaninoff, Maurice Ravel and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who offered examples of a basic concerto structure.

“So, on the classical front, my influences range from Mozart up to the early 20th century; on the soloist front, from the late 19th century, like Joplin, to the 21st, like Vijay Iyer,” she says. “When the time came to create, I was able to take all that stuff I packed away—different styles, different time periods—and structure the piece in different movements. It was fun to create this dream space where Mary Lou Williams and Bud Powell and Cecil Taylor would just meet and hang out.”

For his part, Langrée has been looking at the two remaining works on the program, Gershwin’s An American in Paris and Duke Ellington’s Night Creature, with fresh eyes. In the case of Gershwin, Langrée discusses the piece in almost period-instrument terms, starting with the composer’s original orchestration and recordings of the composer’s own performance style.

“Like many people, I first heard this piece in Leonard Bernstein’s recording, where swing was really crucial to the performance,” says Langrée. “But when we first played the original version, we realized that swing didn’t exist at that time. Listening to Gershwin’s performance, it’s more like ragtime. So as seductive as Bernstein’s version is—and I still love it—I think we should respect what Gershwin actually wrote.”

With Ellington, too, he takes a similarly counterintuitive approach. “Duke Ellington was not just a composer, he was a brilliant tone-poet,” Langrée explains. “Night Creature is incredibly sophisticated music, but when I conducted it with the CSO, the musicians played it in a very pops way, with lots of brassy sonorities. I find this music very poetic, shimmering, mysterious. This time I want to play it like we are painting a wall, putting on a second coat to reinforce the color.”

Read the CSO Sidebar, "Childs, Banks bring the saxophone to center stage, with a dose of poetic inspiration."