Young People’s Concerts: Innovating for a New Generation

by Wajeeh Khan

Do you remember the first time you attended an orchestra concert? Or the first time you heard an orchestra live? For many people this influential first experience with an orchestra probably happened at a young age during a school assembly or class field trip.

These important touchstone moments that, hopefully, turn young people into lifelong music lovers continue today. Several mornings a year, young students from the Greater Cincinnati area arrive on buses, walk up the steps into the magnificent Music Hall, and take their seats for their first orchestra concert.

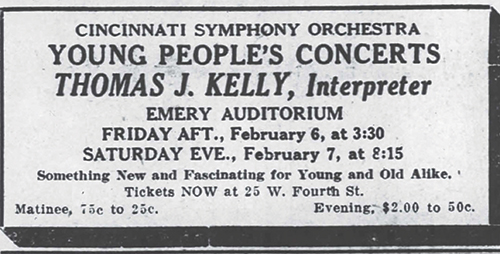

Many may recall (or have seen on YouTube) the iconic conductor and educator Leonard Bernstein’s televised series of Young People’s Concerts (YPCs) with the New York Philharmonic. This series ran for 53 episodes from 1958 to 1972 and helped to popularize and introduce an entire generation to the wonders of classical music. Like many YPCs today, these concerts were approximately an hour long, and they introduced viewers to a wide range of subjects, such as works of great composers, introductory music theory, and musical philosophies. While Bernstein is often credited with the advent of these concerts, you may be surprised to know that the CSO has one of America’s longest-running YPC programs—in fact, the CSO has been holding YPCs featuring the full symphony orchestra since 1920!

100 years later, the CSO’s YPCs are still critical in establishing musical curiosity, appreciation and understanding in countless individuals—especially within musicians. As CSO violinist Stacey Woolley puts it, “If you go out in the community, most people will say that the first time they ever heard an orchestra was at a YPC.” Woolley, who has been a member of the CSO since 1989, credits YPCs in laying the groundwork for his musical journey. “The first time I heard live classical music was at a YPC, when I was around six or seven,” said Woolley.

“After that, I went every year. They opened up a new world for me. I didn’t want them to stop playing! Looking back at it now, YPCs helped to kickstart my love for and association with classical music and Music Hall, which I’ve been going to for over 56 years now—more than a third of its existence!” Over the years, the CSO has continued to make new strides and developments in the presentation and experience of YPCs to further enhance their impact. CSO Associate Principal Cello Daniel Culnan, who has attended YPCs as a child and has been performing in them as part of the Orchestra for decades, notes that YPCs have changed dramatically over the years—and have become far more poignant as a result. “When I was a kid, there was not a lot of connection between pieces,” said Culnan. “Since I’ve been playing YPCs, though, we’ve tended to incorporate a lot more, such as soloists and dancing. It’s not just the Orchestra playing anymore…. It’s a lot more dynamic now.”

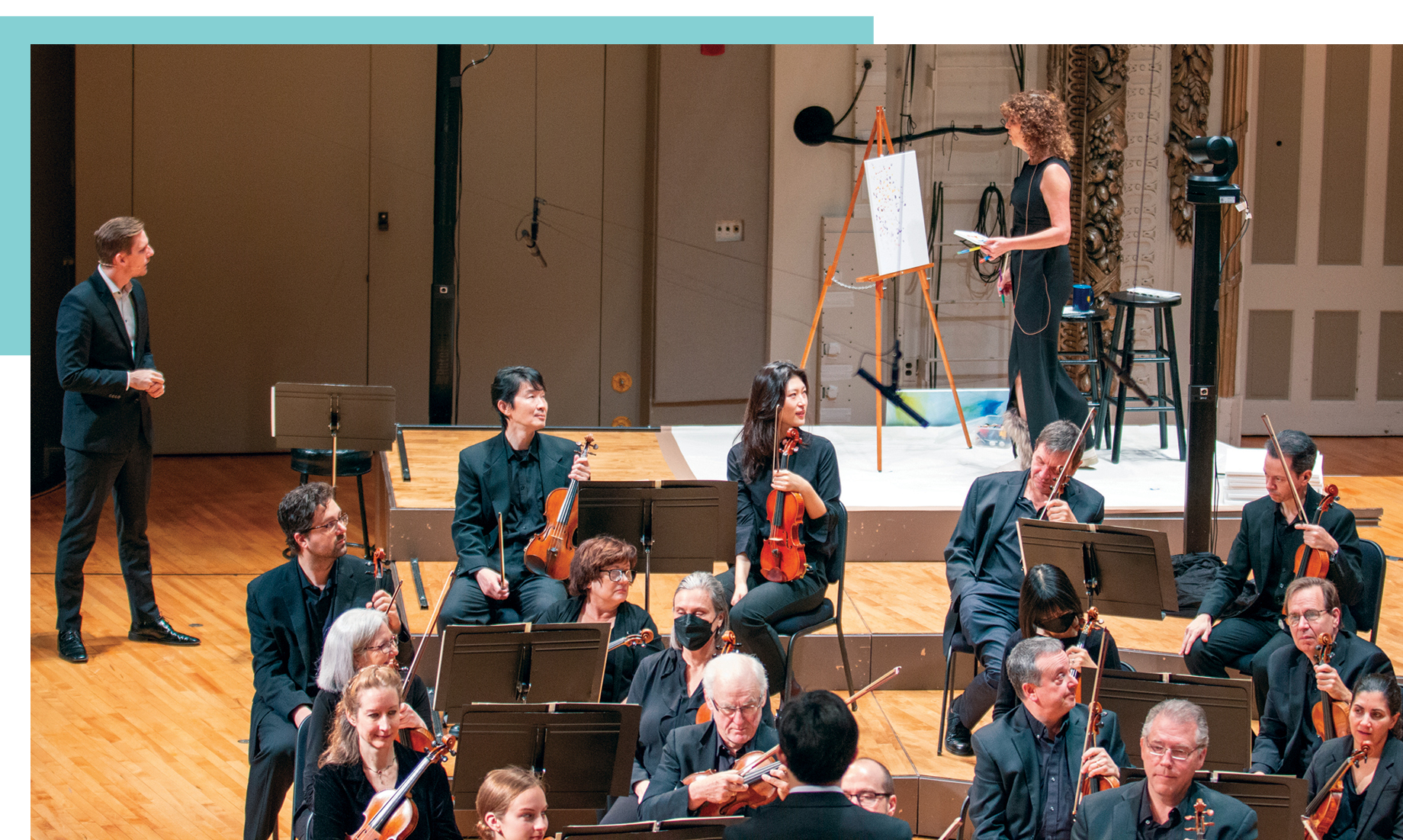

One of the core elements that has propelled the CSO’s YPCs to new heights is inventive programming that emphasizes audience participation and interactivity. “For a long time, there really wasn’t much audience participation, if at all. We were expected to just sit there and be still,” said Culnan. “Now, kids are so much more involved. They’re clapping, stomping, singing, and actually come up on stage sometimes! Seeing all of these kids that are involved and genuinely excited can be so rewarding.” Recently, YPCs such as Dots and Lines and Sonic Architecture have really pushed the envelope to move beyond a simple concert format.

YPCs are a project of the CSO’s Learning Department, where the Assistant Conductors work together with Director of Learning Carol Dary Dunevant to ensure that YPCs are meeting educational goals, trends and benchmarks. Assistant Conductor Daniel Wiley, who conducted Sonic Architecture and hosted Dots and Lines, wanted students to see that musical inspiration and understanding can be found in all sorts of mediums. “All of our education concerts compared composers to other disciplines to establish relatability,” said Wiley. “If you can equate elements of music to elements of other disciplines, it doesn’t seem abstract to kids. It establishes a sense of realism—that music and composition is something that anyone and everyone can be a part of.”

For Dots and Lines, students from grades K–3 compared the music of iconic composers, such as Tchaikovsky and Beethoven, to the work of famous artists like Van Gogh and Matisse. Students interacted with Wiley and visual artists to combine and layer “dots” (shorts sounds) with “lines” (long sounds) to explore how composers and painters use similar techniques.

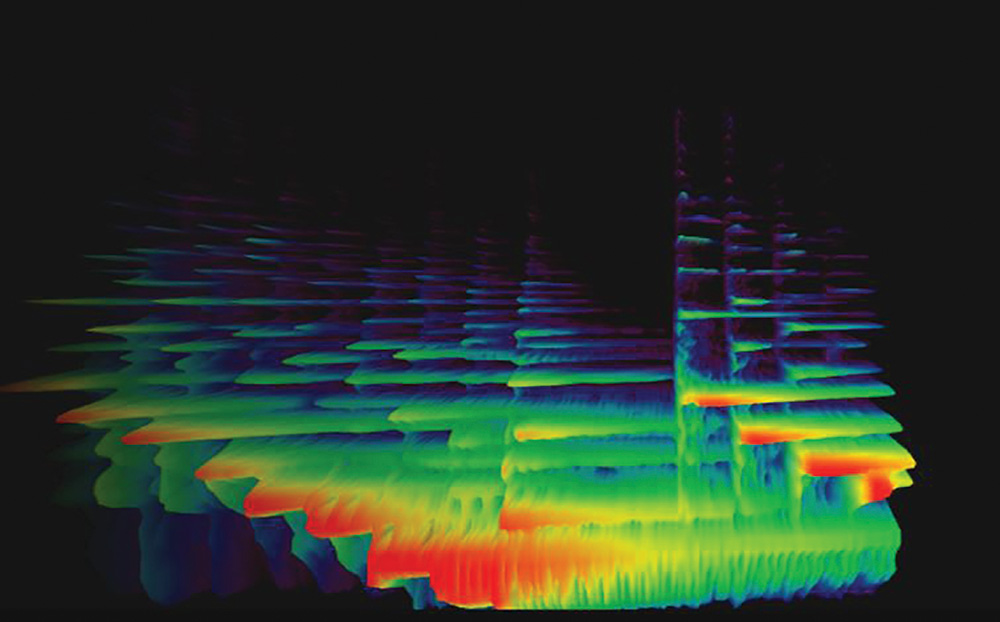

In Sonic Architecture, students in grades 6–12 were able to watch as the Orchestra created visual displays of pitch, duration and amplitude. They then compared the architectural elements of Music Hall to the elements of form used to construct the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. “We knew that form was the architecture of the piece, but then we wondered: what about the architecture we perform within?” reflected Wiley. “Cross-curricular connection is at the core of all YPCs, and we wanted to showcase how both of these concepts could be combined to create something special. We ended up piecing together Music Hall in a sort of ABA form—the left side of Music Hall was A; the center was B, which marks the musical development; and the right side was the return of A.” Sonic Architecture was particularly innovative for its use of a live spectrogram—a visual representation of sound that has time on the “x” axis, frequency on the “y” axis and different colors to represent amplitude. This sound blueprint was mapped onto a 3D rendering of Music Hall, adding vibrant color and visuals to an already dynamic and interactive experience.

The CSO’s upcoming YPC, Once Upon an Orchestra, will give students in grades 4–6 the opportunity to explore connections between creative writing and music composition. Literary devices such as settings, characters, conflicts and resolutions, along with their musical counterpoints, are explored in a way that culminates with a reading of John Lithgow’s The Remarkable Farkle McBride set to music by Bill Elliott.

The importance of Young People’s Concerts goes far beyond the preservation of classical and orchestral music. Young People’s Concerts have the ability to establish a foundation for appreciating art and the artistic experience as a whole. “You have to get people while they’re young and provide them with exposure,” stated Woolley. “Even if they don’t develop a deep appreciation for it, they can still have a fondness for the positive memories that was associated with their experience. And that can build recognition for the impact of music and art.” Culnan, who is retiring this season after 41 years with the CSO, echoed this sentiment as he reflected on being on both the listening and playing ends of the YPC experience:

“It’s hugely important, especially as music programs in schools around the country are not thriving. Not only do YPCs build audiences and awareness for classical and orchestral music for the future, they also open up the minds of children. They can get children to see that there are more aspects to music and, more importantly, to being a human being.”

For more about the CSO’s Young People’s Concerts, visit cincinnatisymphony.org/ypc.