Louis Langrée, Part II Sidebar

by Ken Smith

FIRST OF ALL, this is not your father’s Hamlet, particularly if your family is English.

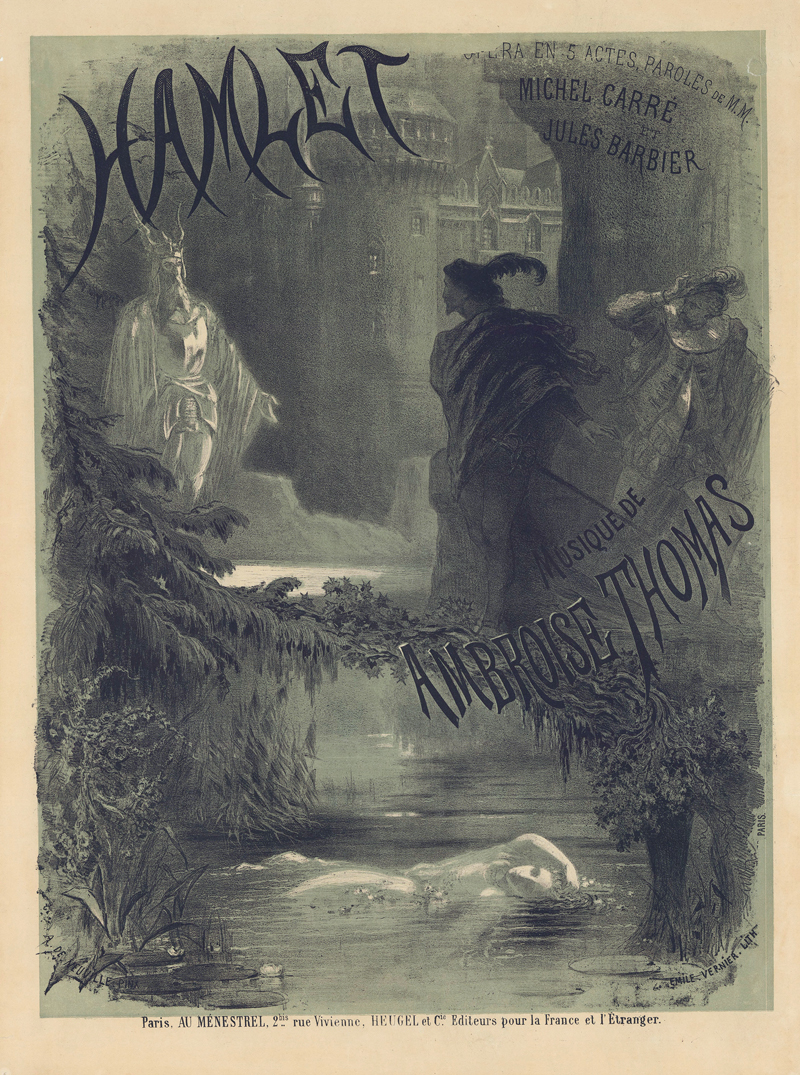

Ambroise Thomas’ five-act opera is covered with many additional fingerprints—not just from librettists Michel Carré and Jules Barbier but also Alexandre Dumas père and Paul Meurice, who adapted Shakespeare’s original drama for the French stage.

For Louis Langrée, arguably the opera’s preeminent living ambassador, a more important tradition to observe is the French operatic repertory. “A century before, Rameau or Gluck would’ve written in a declamatory or conversational manner,” he says. “There was very little difference between singing and acting.” Much later, he adds, you have Debussy and Ravel, “where there is always a musical mix of atmosphere and rhetoric.”

In between was Thomas, who expanded the musical horizons of French opera even while respecting many of its traditions. “How does Thomas express Hamlet’s opening words, ‘Vains regrets’?” Langrée asks. “He has ‘regrets’ descend by a minor third, which sounds pretty regretful, and from there the music conveys an ephemeral tenderness.”

At the same time, though, Thomas often held to the old declamatory style. Where, for ears shaped by the emotional arches of Italian repertory, “To be or not to be”—or in this case, “Être ou ne pas être”—would beg for an aria, Thomas treats Hamlet’s big moment more as recitative. “It is a dramatic scene,” Langrée says, “much the same as Ophelia has a mad scene rather than a ‘mad aria.’ It is a very theatrical way of thinking.”

At the same time, much like his near-contemporary Berlioz, Thomas was also interested in musical effects, from having the ghost of Hamlet’s father singing on a single pitch (representing his trapped soul) to having coronation fanfares performed by off-stage brass and percussion. A key bit of musicological trivia also emerged from his collaboration with Adolphe Sax, the conductor and musical inventor in charge of the Paris Opera’s onstage banda.

“Thomas was always looking for new sounds, and Sax introduced him to one of the instruments he’d recently invented,” Langree says. “That was how Hamlet became the first opera to feature a solo saxophone.”

All of these effects come together to make Hamlet absolutely unique in the repertory, he claims. “Thomas remains a fascinating figure, highly regarded in his own day and—because he was head of the Paris Conservatory when Debussy and Ravel were students—a bridge to the next generation,” Langrée says.

While Thomas’ reputation has long suffered from a puzzling remark by fellow French composer Emmanuel Chabrier (“There is good music, there is bad music, and then there is Ambroise Thomas”), Langrée is justifiably proud of bringing Thomas’ most famous opera back to public attention.

“I am quite proud that Hamlet is now performed much more often than it was 25 years ago,” he says. “If you believe in a piece, you have to promote it and perhaps defend it. All I ask is for audiences to wonder, ‘Wow, why isn’t this piece performed more often?’”