Give Them the Ol’ Razzle Dazzle

By Scot Buzza

“Heaven Nowadays”

“Hello, Suckers!” Propped atop a piano in one of 1920s Manhattan’s most notorious speakeasies, a middle-aged divorcée named Texas Guinan heckled her audience between songs and dirty jokes, emceeing vaudeville acts and plugging bootleg scotch at $25 a bottle. Prohibition be damned—between the hours of 11 p.m. and 7 a.m. she simultaneously ran five different clubs, all under the radar, where cover charges alone ranged from $5 to $25 a head and patrons spent the equivalent of a week’s salary for champagne. Even a pitcher of water was $2—suckers, indeed. But partygoers had few options. The U.S. Constitution had been amended to make alcohol illegal, and only those lucky few knew where to find the underground clubs, buttressed behind soundproofed walls, where you could buy booze, sex and more.

This deliciously sleezy milieu provided the backdrop for Chicago, in which a cadre of crooked lawyers and an opportunistic press feed sensationalism and vicarious thrill to a hungry public. Through the language of vaudeville and jazz, Chicago adopts the very form it lampoons, satirizing the media circus and telling us something ugly about ourselves along the way. The Broadway version of Chicago has little in common with the long list of musicals that glamorize show business. In fact, we, the audience, revel in the decadence: we find ourselves cheering for Velma and Roxie, we applaud the Merry Murderesses in the Cook County jail, and we ridicule Amos, the only selfless character on stage.

“You Can Even Marry Harry and Mess Around with Ike”

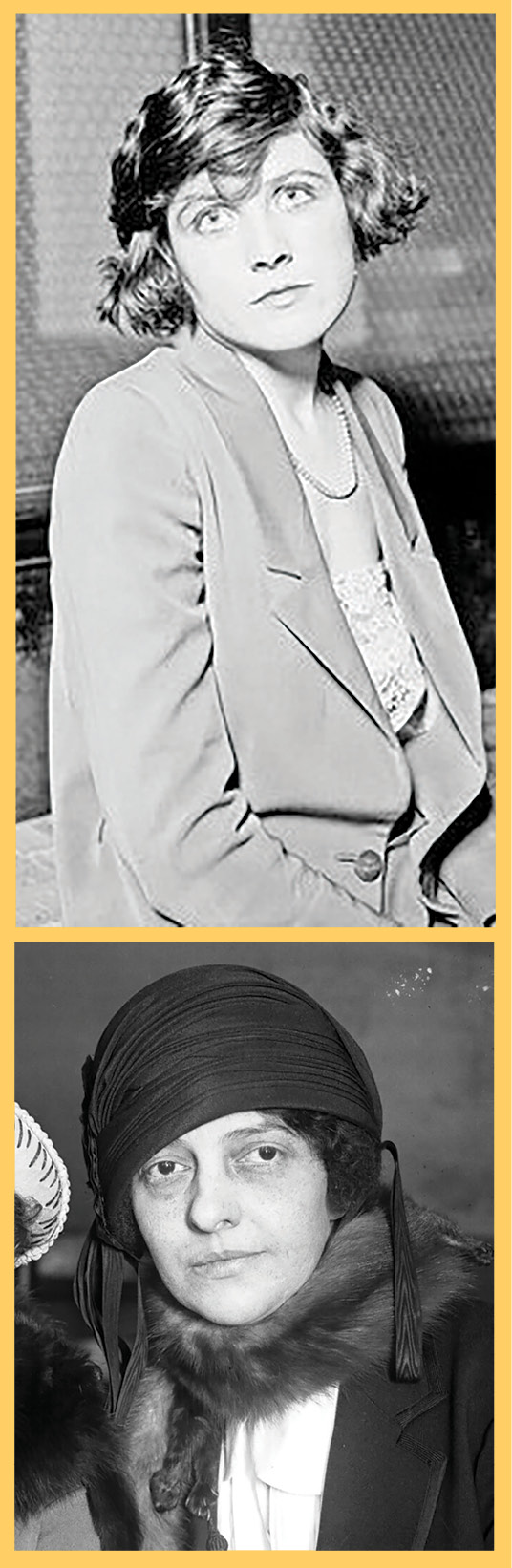

Chicago was originally a 1926 stage play by journalist Maureen Watkins, based on several murders of the previous year. Jazz singer Beulah May Annan, the basis for the character Roxie, had been the wife of a mechanic. She shot her lover when he jilted her, and then she convinced her husband to take the rap. The 1926 Chicago script incorporated parts of her testimony verbatim, including the revelation of her pregnancy—conveniently forgotten after her acquittal. The story of Belva Gaertner, the true-life basis for Velma, follows along parallel lines. A cabaret singer who murdered her husband, she was acquitted when she claimed to remember nothing about the incident. Lawyer W. W. O’Brien, the real-life counterpart to the unctuous Billy Flynn, reportedly loved the publicity generated by his clients, and he basked in the attention after the original stage version of Chicago opened.

The 1942 film version of Maureen Watkins’ play was titled Roxie Hart. Designed as a Ginger Rogers vehicle, the movie overhauled the plot and incorporated several hilariously irrelevant tap dance numbers. The ending, rewritten to conform to the Hays Code content guidelines, showcased a rehabilitated and happily married Roxie as the glowing mother of six children.

A decade later, actor/dancer Gwen Verdon and husband Bob Fosse began a long campaign for the rights to the story and, in 1975, finally crafted the Broadway musical version. Fosse built the production on a score created by composer John Kander and lyricist Fred Ebb, with Verdon starring alongside Chita Rivera. The team chose to focus on vaudeville as the vernacular of the story, and on the idea of show business as the central metaphor for vice.

“How Can They Hear the Truth above the Roar?”

If music director Rob Fisher sounds like a sociologist when he talks about Chicago, it may be because of his long history with the show. Beginning several decades ago with his music direction of the 1996 Encores! production in New York’s City Center, he oversaw the subsequent transfer of Chicago to Broadway, where it has become Broadway’s longest running revival. Since then, he has supervised productions in many different countries, translated into many different languages. Much like the version seen here on the stage of Cincinnati’s Music Hall, the Encores! revival stripped away many of the external elements to place the music and the story at the center, and in so doing, brought new layers of significance to the surface. Fisher says about that revival:

The simplicity of that production was that it did focus on the score, but the time was ripe—we’d just had the O.J. trial. And I feel like the focus when Fosse did it was ‘aren’t people slimy’ and ours really focused on celebrities getting away with all kinds of stuff just by being celebrities. Doing foreign productions of it has been interesting because they all love to make fun of that particular kind of Americanism, of us elevating our celebrities to this ridiculous status. And that’s what Chicago is about. You “give them the ol’ razzle dazzle” and you can get away with anything. You can “shoot someone on Fifth Avenue.”

Audiences understood the newfound relevance immediately, and when Velma thanked the audience for participating in the charade—“We are living examples of what a wonderful country this is!”—it was a punch in the gut. Newsday deemed the new interpretation “edgy, erotic, cynical, funny, nonstop stylish and, though based on a 21-year-old show, so prescient about ‘90s justice, the press and celebrity that it’s almost eerie.” Ben Brantley observed, “all the world’s a con game, and show business is the biggest scam of all,” and The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote, “Chicago is revealed not just as the musical classic it is, but as a show with particular resonance for our time.”

“A Whole Lot Greater than the Sum of His Parts”

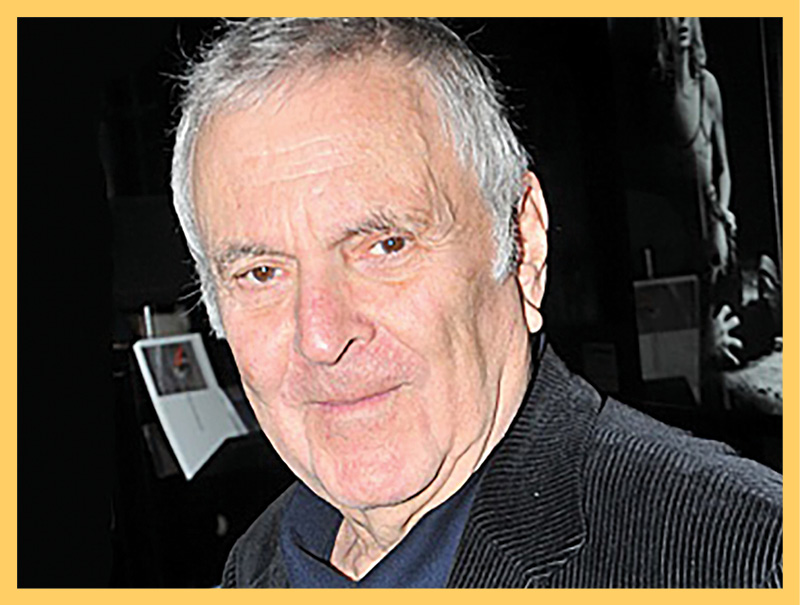

1975 Broadway musical version of Chicago, with lyricist Fred Ebb.

John Kander’s score is the lens through which the audience experiences the story. In his original orchestration, certain instruments in the orchestra had iconic value: the sexy trumpet opening illustrating the “anything goes” morality of the times, the ironic solo violin whenever a particularly distasteful character asked for sympathy, and the Hungarian motives for the exotic foreign murderess, Hunyak, among others. Fisher agrees that expanding the original Broadway pit version into the full symphonic version is similar to replacing 12 crayons with a box of 64.

“The heft of the orchestra really supports the story—it becomes more like a big Hollywood musical having that big orchestra. It really works.”

In his estimation, nothing is lost in translation because of the public’s familiarity with the music:

“The audience at Encores! was even applauding the vamps, they were applauding the intros to the songs because they were so excited to hear them. Now, this many years later, it’s happening again. They know the show, they know what’s coming. Also, they sing along! A symphonic audience sings along!”

“Sequins in Their Eyes”

In the world of Chicago, contemporary society prizes “murder, greed, corruption, violence, exploitation, adultery and treachery—all those things we hold near and dear to our hearts.” Publicity thwarts justice. Courtrooms are circuses and lawyers are celebrities who perform instead of litigate. The anti-heroines are ultimately acquitted not because of their innocence, but because of their ability to manipulate public opinion with a wink and a wiggle. We will look past the most egregious of sins, they tell us, as long as we have something shiny and entertaining to distract us. “Exit music, please.”

Synopsis

The place is Chicago, Illinois. As the orchestral vamp begins, the roaring ‘20s are in full roar: the gin may be cold, but the jazz is hot. The Overture ends and we meet vaudevillian Velma Kelly, a first-tier star who has just murdered her husband and her sister after catching them in flagrante delicto. Velma invites the audience to bask in the decadence of the times (“All That Jazz”) while the story of chorus girl Roxie Hart unfolds. Roxie has just been jilted by her lover, nightclub owner Fred Casely, and so she does what any self-respecting Catholic girl from Sacred Heart would do: she shoots him point-blank and kills him.

Roxie convinces her husband, Amos, that Fred was a burglar, and she sings of his simple-minded devotion to her (“Funny Honey”) when he agrees to take the rap. But when the police reveal that Fred was Roxie’s lover, he decides to let her fend for herself. Roxie faces the repercussions of her actions in the women’s block of the Cook County Jail, where she first encounters not only Velma Kelly but also a group of other women who murdered the paramours who wronged them (“Cell Block Tango”). Prison matron “Mama” Morton presides over the jail as her personal domain, ruling with an iron fist and enforcing a system of mutual exploitation (“When You’re Good to Mama”) according to a moral code as decrepit as that of her charges. Through her connections to the outside world, Mama Morton has helped Velma win the sympathy of the public and is already working as her agent to book her vaudeville appearances after her acquittal. Velma is furious at the arrival of Roxie, who threatens her place in the limelight.

Lawyer Billy Flynn arrives at the prison, fêted by his clients in the women’s wing, who coo and sigh as he professes, “All I Care About is Love.” Billy has agreed to take on Roxie’s case after extorting money from Amos, and he immediately begins re-writing her story for publication by the sympathetic tabloid columnist, Mary Sunshine, who always sees “A Little Bit of Good in Everyone.” Billy puppeteers a conference for the mainstream press, turning it into a de facto ventriloquist act with Roxie merely paying lip service as Billy dictates a new version of the “truth” for the public (“We Both Reached for the Gun”).

Roxie and her trial have become the new cause célèbre of Chicago, while Velma finds that her headlines have disappeared, her trial date has been postponed, and her career plans have stalled. Velma, out of desperation to stay in the public eye, works to talk Roxie into recreating her sister act (“I Can’t Do It Alone”), only to find Roxie’s own place in the headlines threatened by the latest sensational crimes of passion. Roxie and Velma each realize that they can trust no one (“My Own Best Friend”) and, in an inspired twist, Roxie announces to the press that she is pregnant, putting her in the headlines once again.

Following the Entr’acte, Velma greets the audience with “hello, suckers!” and laments the lucky streak Roxie seems to be enjoying (“I Know a Girl”) despite her obviously false pregnancy (“Me and My Baby”). Amos, still gullible, looks forward to fatherhood until Billy prompts him to do the math and understand that he is not the father of the baby. Dejected and emotionally exhausted, Amos questions his own worth (“Mr. Cellophane”) before apologizing to the audience and shuffling off stage. After Cook County executes its first female prisoner in 47 years, it seems as though Velma may be convicted, after all. She struggles to win back Billy’s attention and reignite his interest in her case (“When Velma Takes the Stand”). Billy has a talent for blinding juries with his showmanship (“Razzle Dazzle”), but when he gives Velma’s strategies away to Roxie, Velma and Mama Morton are left questioning decorum and loyalty (“Class”).

In a brilliant act of manipulation, Billy gets Roxie acquitted but, as the verdict is pronounced, press attention shifts to a more sensational crime and Roxie’s fleeting celebrity is over. After admitting the fake pregnancy and dismissing the ever-loyal Amos, she faces the challenge of regaining public attention. She and Velma pull themselves up by the bootstraps, create a team act (“Nowadays”), and swap their aspirations of fame for notoriety. They dance to thank the audience for their support (“Hot Honey Rag”), extol the virtues of the American media, and join the company for a cynical final reprise.