From Darkness to Light: Opening the First Full Season in Three Years

by Ken Smith

The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra has many reasons to launch its 2022–23 season with Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 on September 24 and 25. “Frankly, I don’t know anyone who doesn’t deeply love this music,” says Music Director Louis Langrée. “Anytime you hear this piece, it becomes a celebration.”

And rarely, he adds, have musicians and music lovers alike needed a celebration so badly. “There is always some musical work to mark a spiritual return to the world,” Langrée maintains. “Mahler’s Second is that kind of piece, moving from darkness into the light. It resonates as a collective experience. After this time of isolation, this transformational ritual feels necessary.”

But let’s not forget the symphony’s additional moniker. Is there any piece in the orchestral repertory able to mark a return to full public life more clearly than the “Resurrection” Symphony? For Langrée, the event is nothing less than a full justification of a concert as a uniting and communal experience. “At the beginning of the pandemic, we all thought that streaming was the solution, the way of the future,” he reflects. “After all, we can reach more people in one stream than we could in a whole concert season. But streaming has proven to be a plus, not an ‘instead of.’ Nothing can replace the artistic and spiritual experience of musicians and audience members being together in the same time and place.”

Not only does Mahler’s Second Symphony utilize the full forces of the CSO, but it also features the May Festival Chorus (an institution leaving its “high-risk” Covid status just in time for its 150th anniversary season), May Festival Youth Chorus and Xavier University Choir. So, too, does it welcome the return of two soloists with very special relationships to the Orchestra.

“Soprano Joélle Harvey and mezzo-soprano Kelley O’Connor were not selected by chance, but because they have a special connection with the Orchestra,” Langrée maintains. “The last time I conducted Das Lied von der Erde in Cincinnati, it was with Kelley. The first time we did Beethoven’s Ninth, it was with Kelley. She has been a large part of my epic journey here.”

It was Joélle Harvey’s essence that remained over the last couple of years, however. The soprano was the last soloist scheduled to perform with the CSO at Music Hall the week of its pandemic closure. Langrée recounts that fateful day watching Jonathan Cohen rehearse Handel, when CSO administrative staff members Paul Pietrowski and Robert McGrath interrupted the proceedings to say, “The rehearsal is over. Please take your belongings because you won’t be coming back soon.”

“Joélle’s presence hovered in our halls for months,” Langrée says. “Not only did her voice still resonate in the air, but her name remained hanging for months on the dressing room door—right below the sticker that said ‘Cleaned & Sanitized.’ So, you see, in many ways, this program is all wonderfully symbolic.”

■ ■ ■

Only a few days after Mahler’s Second Symphony (Sept. 30/Oct. 2), Langrée returns to more unfinished business, namely recording Christopher Rouse’s Symphony No. 6, which had its world premiere in Music Hall in October 2019. “Of all the commissions and premieres I’ve conducted, this experience was one of the most powerful,” the conductor recalls. “Both for the music and the circumstances.”

Having commissioned a large piece for the CSO anniversary season, Langrée had expected “a musical birthday cake with some fireworks,” he says. Instead, he received a dark, intense probe of the composer’s emotional core. The conductor had so many queries about structure and content that he compiled a single list so that Rouse could answer them all at once.

But as the premiere date approached, the Orchestra was informed that Rouse’s health would not permit him to attend. Then came abrupt word of the composer’s death, at age 70, of renal cancer. “This was a total shock,” Langrée recalls. “I’d never met him. I had so many questions, and now no possible chance of a dialogue.”

Rouse did, however, leave a program note—to be released posthumously—answering many of Langrée’s urgent questions. Suddenly the music’s content became abundantly clear: The composer who had spent much of his career musically recounting the passing of others—his Pulitzer Prize-winning Trombone Concerto (1990), the first in his so-called “Death Cycle,” was inspired by the late Leonard Bernstein—publicly admitted that the death documented in his final piece was his own.

Langrée had already noted how Rouse’s expressive phrases, often soaring directly into the heart, finally descend to a single drone in the double bass. “The note just continued, without any effects or ornamentation, holding until it was suddenly ‘power off’,” he says, now understanding that the music represented the composer’s lifeline. “The effect was overwhelming.”

Even without personal interaction with the composer, Langrée says he found “a mysterious connection to the composer” through the music. “I don’t know how to explain this, but the first performance didn’t feel like a normal premiere,” he says. “It felt as if this piece had existed for some time, that it was already part of the repertoire—that is was already a part of the story of the CSO.”

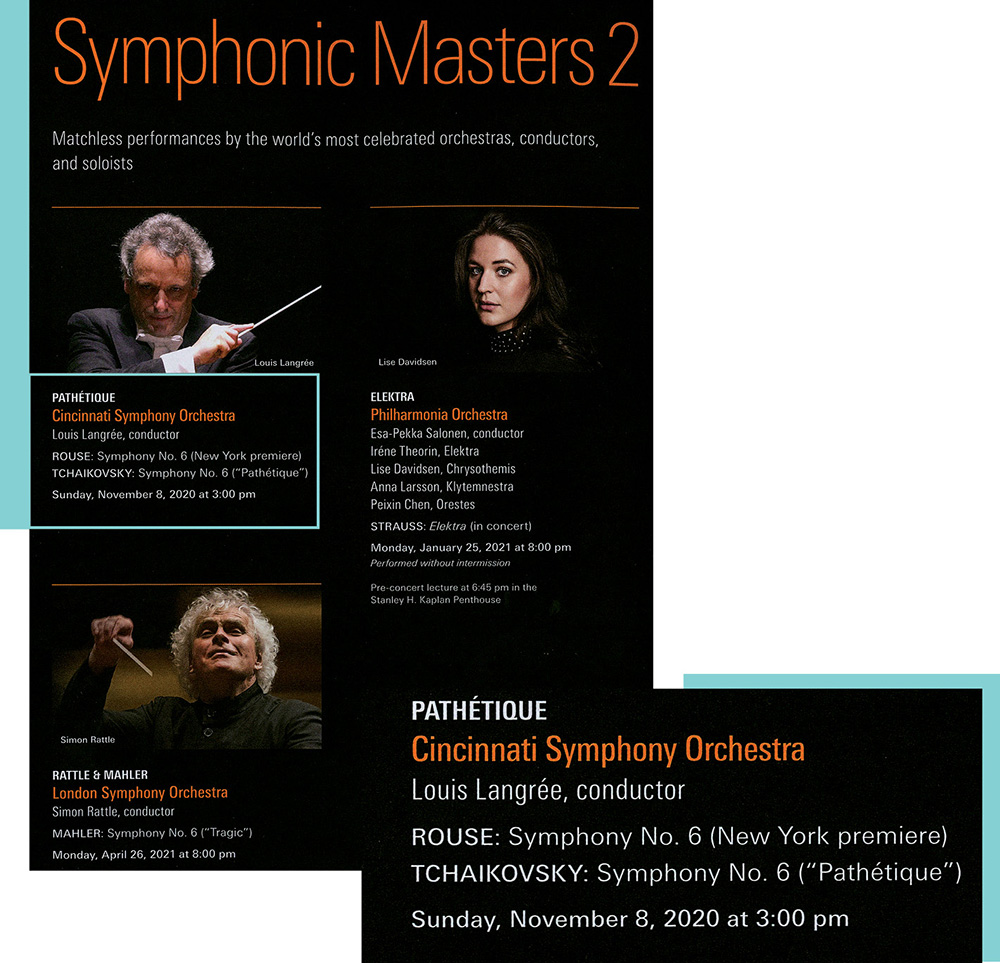

Plans to give the New York premiere at Lincoln Center as part of the Great Performers Series, pairing it with Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6, fell by the pandemic wayside, although the CSO will finally record Rouse’s final symphony soon after the final October 2 performance. “These are not merely two ‘sixth’ symphonies, they are also their composers’ final message,” Langrée says. “We don’t know if Tchaikovsky knew it would be his last, but Christopher Rouse certainly did. They both end with adagios and share a similar emotional world.”

Langrée also credits Tchaikovsky not just with writing infectiously beautiful music but also changing the course of symphonic music. “After Beethoven’s Ninth, composers didn’t know what to do,” he says. “Some followed the literary route, like Berlioz with Symphonie fantastique. Others like Bruckner went in a more spiritual direction. Even Mahler’s Second often follows the structure of Beethoven’s Ninth, starting in a major key and ending in minor, with a chorus at the end.

“The composer who really opened the path was Tchaikovsky,” he continues. “Ending a symphony with an adagio was a revolutionary statement. I don’t think Mahler would have dared to finish his Third Symphony with an adagio if Tchaikovsky hadn’t already shown the way.”

■ ■ ■

The Sixth Symphony of yet another composer features heavily a few weeks later when guest conductor Michael Francis takes the podium October 29 and 30. “It’s always lovely to bring music from your homeland,” says the British-born Francis. “This year, marking the 150th anniversary of Vaughan Williams’ birth, is a major milestone.”

Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Symphony No. 6, composed during and revised immediately after the Second World War, is a “30-minute masterpiece exploring the darkest horrors of humanity,” Francis says. “The primal scream of the first moment—a real Edvard Munch kind of explosion—can be really quite shocking to listeners who only know the language of his Lark Ascending or Tallis Fantasia. This music shows a completely different side.”

Unfolding in four unbroken movements, the symphony’s second movement “feels like a kinetic, military tank invasion,” the third “like being thrust into a militaristic tumble dryer,” Francis says. Many listeners have likened the fourth movement—“pure musical nihilism, devoid of any expression for nearly 10 minutes”—to a nuclear apocalypse, or the shock of the atomic bomb. “Not even Shostakovich wrote music so unrelentingly powerful,” Francis claims. “It’s not just recounting the horrors from the last century, but reminding us what we should all remember today.”

Finding a companion piece to match that intensity might seem challenging, but Francis has bookended Vaughan Williams’ Sixth with Andrzej Panufnik’s rarely performed Sinfonia Sacra, a piece Francis first conducted on a 2014 program with the London Symphony Orchestra when he stepped in for the late Sir Colin Davis. Panufnik, who fled Soviet-controlled Poland for England in the mid-1950s, briefly became the Chief Conductor of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, but his musical legacy was mostly in composition. Sinfonia Sacra, his third symphony, marked a thousand years of Christianity in Poland.

“The piece opens with an antiphonal fanfare with four trumpets blaring like epic horses of the apocalypse,” Francis says. Once the intensity dies down, the piece builds again over the next 15 minutes, the music heavily quoting the Bogurodzica, the first known hymn in Poland. “This was the music of someone living apart from his country, trying to find beauty in crisis and giving strength to his people. And his idea of strength was that a militaristic call to arms must also be balanced by prayer and a spiritual core.”

Balancing the rest of Francis’ program is the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini by Rachmaninoff (“another composer living apart from his country,” he says) and Charles Ives’ elegiac Unanswered Question, where a solo trumpet unfolds in a less forceful, more contemplative context.

■ ■ ■

The CSO brass, well-honed by its legacy of fanfares, also plays heavily into Richard Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra, which Langrée will pair with Schumann’s Piano Concerto with soloist Hélène Grimaud October 21–23.

“The CSO has a special connection with Richard Strauss,” Langrée states. “Strauss is simply in this orchestra’s DNA.” Strauss himself conducted his Death and Transfiguration, Don Juan and several songs at Music Hall in 1904; rather more recently, Langrée has led the Alpine Symphony, Don Juan, Metamorphosen, and The Four Last Songs with soprano Renée Fleming.

Opening his program with the Schumann Concerto, “the pairing with Strauss will be a full showcase of CSO musicianship,” Langrée says. “This is not a symphonic concerto, like Brahms’ First,” he says. “It’s more like chamber music. Particularly with a soloist like Hélène, it will be a constant kaleidoscope between collective and personal music-making.”

Langrée dipped a toe in Also sprach Zarathustra, a tone poem inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophical novel, when he conducted the opening of the work at Lumenocity, the CSO’s former high-tech outdoor sound-and-light show. “The beginning of the piece is such a blockbuster, famous even to people who have never been to a classical concert,” he says. “But Zarathustra is a masterpiece that goes well beyond the opening fanfare.”