Being Concertmaster is Much More Than “Give Me an A”

by Anne Arenstein

When the sounds of pre-concert warm-up subside, either violinist Stefani Matsuo or Felicity James stands and gives Principal Oboe Dwight Parry a nod to play the familiar concert “A” pitch for final tuning: first the winds and brass and, finally, the strings.

Matsuo is the CSO’s Concertmaster and occupies the Anna Sinton Taft Chair. Felicity James serves as Associate Concertmaster and holds the Tom and Dee Stegman Chair. Signaling for the tuning pitch is the most visible part of their jobs, whose responsibilities are best summed up by Matsuo:

“I’m basically second-in-command to the conductor.”

The concertmaster’s unseen work is extensive, intense and ongoing, beginning with preparing the orchestra for each scheduled concert months before performance. When Matsuo isn’t scheduled as concertmaster, James takes over. The job calls for time, personnel and logistics management, as well as knowledge of performance practices, communication skills and lots and lots of practicing.

“There’s a fair amount of preparation,” Matsuo confirmed with no irony.

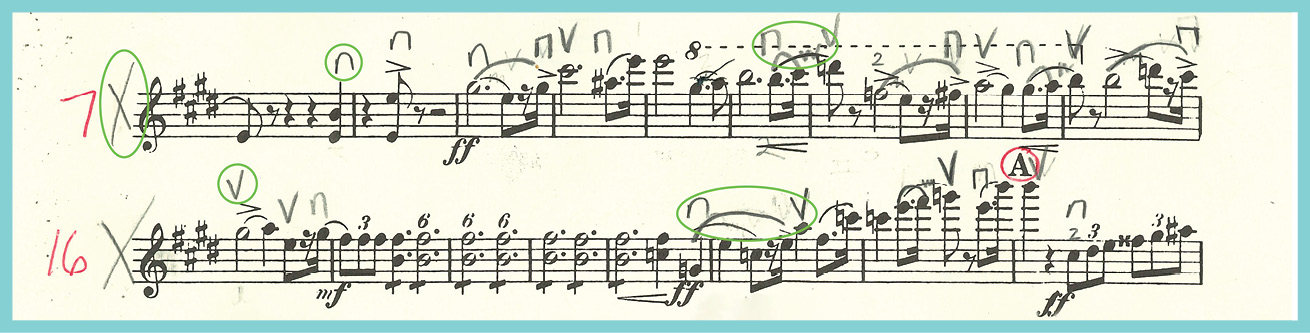

The first step is studying the program’s scores and marking bowing for strings. “Bowing is the direction, either up or down, used by string players,” Matsuo explains. “Some changes may be required, but we try to be unified so our sound is as seamless as possible.”

“Our library staff is amazing,” she adds. “They get us the scores quickly, and once the concertmaster has finished bowings for the first violins, the scores go to the principals in the other string sections.”

This season, with Louis Langrée conducting only six subscription concerts, there are many more guest conductors, which Matsuo and James acknowledge is a challenge, although an exciting one.

“Every guest conductor has their own unique style of communicating. Some conductors trust the orchestra 100 percent with everything and the preparation that we do before we go into rehearsals,” Matsuo says.

“Others provide their own scores and their own parts with bowings so that they can begin rehearsals from a place where they’re comfortable.”

With each guest conductor, a series of email or Zoom conversations precedes the conductor’s arrival in Cincinnati.

“It helps us get a sense of their vision,” Matsuo says. “Our Orchestra is super flexible and can adjust playing styles based on the conductor who’s here. That’s what our Orchestra excels at.”

The concertmaster’s leadership may be imperceptible to the audience, but, to a back row brass player or percussionist, it can be a subtle but vital gesture.

“Little details are super important,” Matsuo says. “A wind player might say, ‘We’re playing this together, but I need to take a breath or I’ll pass out, so give me a split second of time.’”

“Or someone will tell me they can’t see the conductor in a particular spot and ask for me to check in visually to make sure they can see me, so we’re in sync.”

“It can be as simple as raising an eyebrow.”

James sits next to Matsuo and describes her role as helping make Matsuo’s job easier:

“If Stefani changes the bowing or cues an entrance in a certain way, it’s my job to mirror exactly what she’s doing, so if someone sitting in the back can’t see her but they can see me, I should be doing exactly what she is.”

Preparation varies from concert to concert, but nothing prepared Matsuo for the Covid shutdown and the sudden shift to livestreamed performances of entirely new and previously unperformed works.

“As a result of this pivot, I had to familiarize myself with new repertoire in order to prepare parts with bowings, as well as lead my section and the orchestra,” she recalls. “This was both a challenge and a treat, as it opened my eyes and ears to pieces that I may not have had the opportunity to play otherwise.”

One of the most memorable performances was Anthony Davis’ You Have the Right to Remain Silent, featuring former CSO Associate Clarinet Anthony McGill, now the New York Philharmonic’s principal clarinet.

“It was incredible having Anthony Davis and Anthony McGill here to lead us all through the piece. Working with them helped us to understand the work and clarified any musical questions we might have had,” Matsuo says.

Throughout the livestreamed season, a constant challenge was to maintain a unified sound with increased distance between players, especially with plexiglass barriers surrounding some musicians.

“It was a steep learning curve,” Matsuo notes. “We also had to adjust our playing for microphones that were close to us, as opposed to projecting into a hall full of people. Everyone navigated the challenges beautifully.”

As in-person concerts resumed and the CSO returned to a full season, world premieres of commissioned works originally scheduled for the 2019–20 and 2020–21 seasons were added to the schedule.

“There were times when I felt like we were doing a commission every week as we came out of Covid,” Matsuo recalls. “A new work brings unique challenges for everyone.”

“When we get pieces that are unidiomatic, we have to be creative to figure out the best way to approach something that might not be comfortable.”

“Sometimes it’s asking, ‘Are you really sure you want it this way? It might sound better if we do this.’”

“Some composers will be flexible, and others will want that gritty struggle.”

Felicity James experienced different demands when she served as concertmaster for the CSO’s performances of Ambroise Thomas’ Hamlet in November:

“There are a lot of moving parts in opera, including the tech aspects, so it’s crucial for the concertmaster to make things easier when there’s so much going on.”

“The conductor may not have the time to notice all of these small things, and my job is fine-tuning something the conductor might miss,” she adds. “Someone may not always see a singer, so it’s even more important to physically lead to create that unified sound.”

Matsuo and James exude confidence in themselves and in each other. They are rarities in American orchestras (and, indeed, in orchestras worldwide) as women under 40.

“There are just a handful of full-time orchestras with women as concertmaster or associate chair,” Matsuo says. “As more orchestras shift to screened auditions, I hope that we’ll see more women take on those roles.”

Matsuo joined the CSO’s second violin section in 2015 and won the associate concertmaster audition in 2018. The following year, she successfully competed for the concertmaster position. She studied at the Cleveland School of Music and Juilliard.

James joined the CSO in 2022 after serving as associate concertmaster for the Minnesota Orchestra for four years after studying at the Colburn Conservatory of Music.

Both have extensive experience as chamber musicians and soloists. Matsuo performed Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 4 with the CSO in May 2019, opened the 2021–22 season with Brahms’ Scherzo from “F-A-E” sonata, has performed Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 with her colleagues this season and will perform the substantial violin solo when the CSO performs Richard Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben on March 23 and 24.

Solo repertoire is a big part of the concertmaster audition process and, as both point out, the extent of job responsibilities becomes apparent only after winning the audition; today’s concertmaster responsibilities have evolved since the 18th-century European tradition of the first violinist leading the orchestra, as Mozart had done.

“You have to learn how to navigate from your first day on the job,” Matsuo says. “We’re so focused on the audition aspect that we don’t think about how many other aspects there are!”

One of the most crucial skills in a concertmaster’s toolbox is leadership, a skill not taught in conservatories or in private lessons.

“There’s a very steep learning curve and you have to learn from your mistakes early on,” Matsuo acknowledges.

“Fortunately, we work with great colleagues. Not all orchestras are as friendly as the CSO, so I haven’t had a lot of sticky situations to deal with.”

So, at a concert’s conclusion, when the conductor shakes the concertmaster’s hand, it’s more than a courtesy: it’s an acknowledgement of a job well done.

Matsuo and James credit their success to their unique chemistry as stand partners, musicians and friends, and to the support of their colleagues in the CSO.

“It’s an incredible experience for me to sit next to someone like Stefani, a strong female whom I respect,” James says, adding that she initially felt her age might present difficulties.

“As a young woman, it can be a bit intimidating with colleagues who have so much knowledge and so much experience,” she notes. “But it’s been a great learning experience getting to know my colleagues. They share so much.”

“It’s one of the best groups of people I’ve ever worked with, and it makes my job easier.”

Matsuo agrees: “I wouldn’t have wanted to take on this role in any other orchestra.”