Symphonic Symbolism

Richard Strauss took representational music to new heights with his instrumental tone poems

by Hannah Edgar

Leave lofty storylines to the Richards—Wagner and Strauss, that is. The latter brought the representative specificity of the former’s operas to concert music, and in doing so brought the tone poem genre to new heights. Somehow, even without text, Strauss’ tone poems don’t mince words. His Ein Heldenleben (“A Hero’s Life”), heard on Sir Mark Elder’s CSO program (March 23 & 24), was, along with Symphonia Domestica, his most autobiographical tone poem, though Strauss denied any parallels between the titular hero and himself. He wrote both shortly before he decisively turned his attention to opera, around the turn of the 20th century.

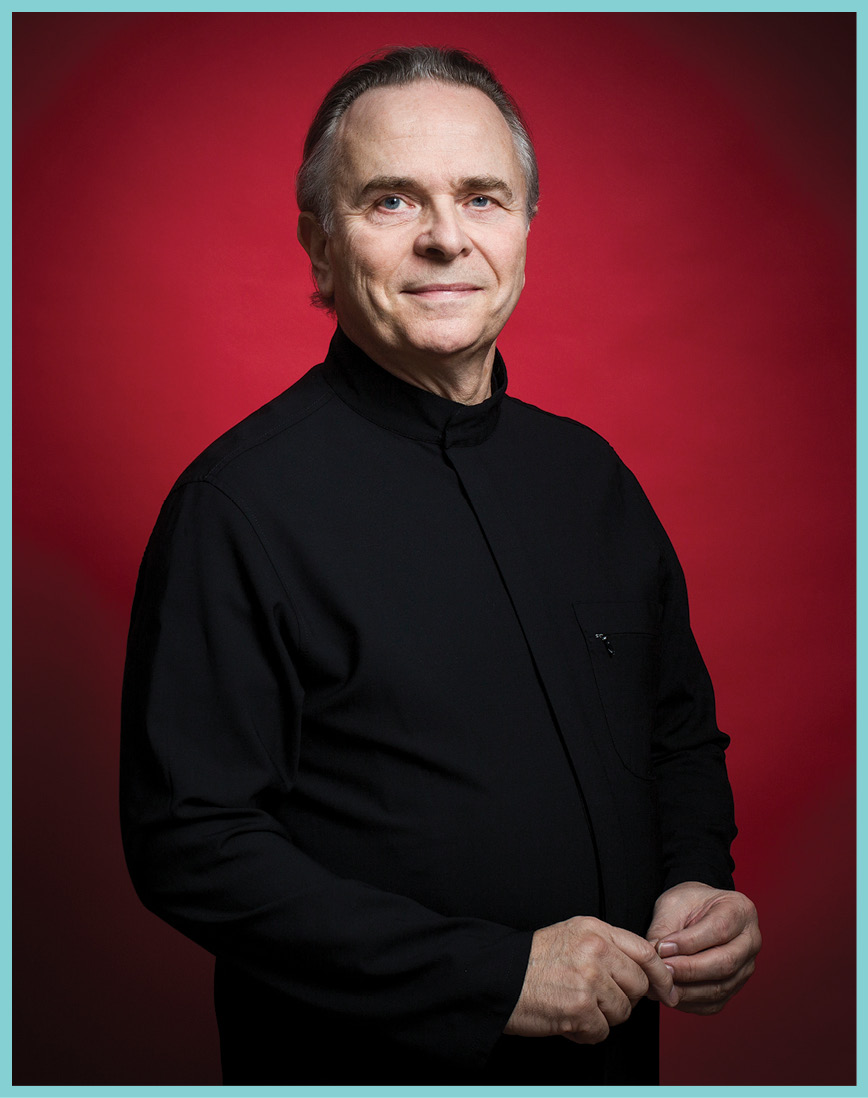

“One feels often that [Strauss] is on the threshold of real greatness,” Elder told Fanfare. “There are times when, I feel, he touches it. He was like a magician with the orchestra. But like he said in London when he was an old man, ‘I’m not a first-class composer. I am a first-class second-class composer.’”

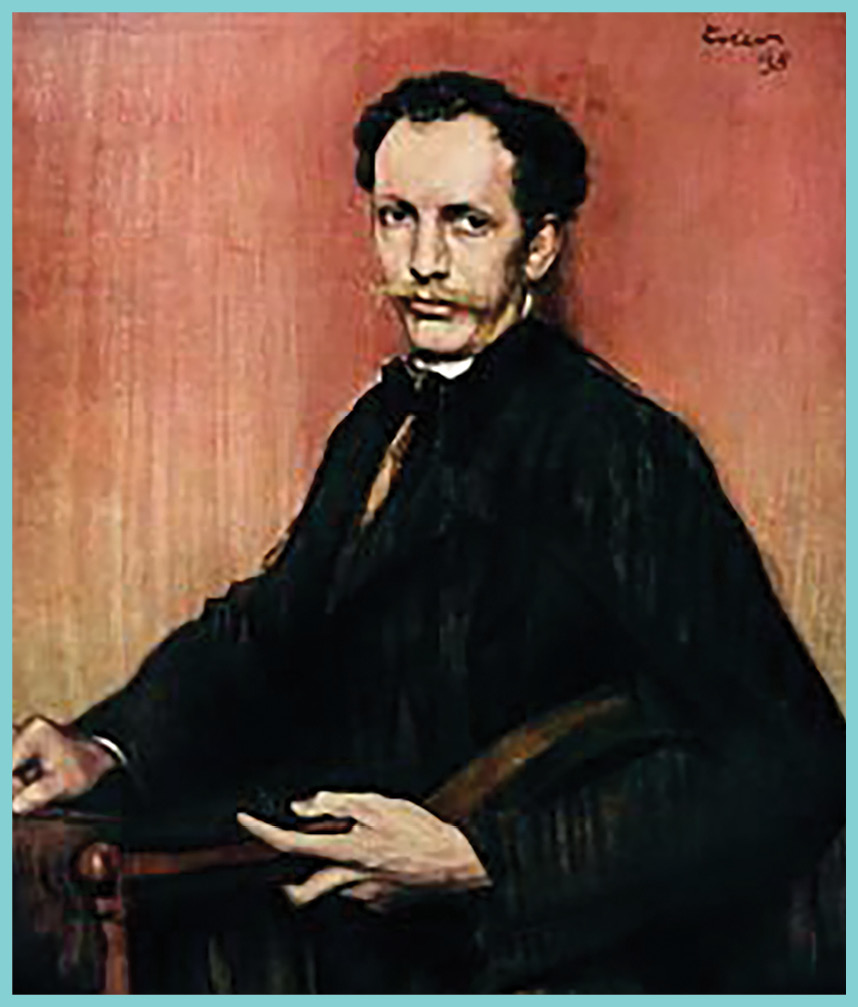

The composer against whom Strauss is most often compared, usually unflatteringly, is, of course, his idol Wagner. Strauss came of age at a time when German Romanticism split into aesthetic factions represented by Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann (traditionalists) and Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt (radicals). Although the totality of musical creativity in the second half of the 19th century was hardly so black and white, the period’s bitter ideological fissures were very, very real. Strauss’ father, a star French horn player in Munich’s court orchestra, loathed Wagner’s music so completely that he refused to stand during a moment of silence for the recently departed composer, despite having played principal horn for several of Wagner’s premieres. The teenaged Strauss attended one of them, Parsifal, in Bayreuth, at his father’s begrudging invitation. He left transformed. Alas, Wagner’s music was verboten in the family home, so Strauss had to develop his mature, unrepentantly Wagnerian harmonic dialect by studying the scores in secret.

Like Strauss, Elder had his first transformative encounter with Wagner’s music as a teenager, playing the overture to Tannhäuser—the very same overture he has programmed for his CSO concerts—with a youth orchestra as a 14-year-old bassoonist.

“I can never forget the experience of being in that noise, right at the beginning,” he says.

Now, having conducted the entire opera over the course of his career, Elder feels any performance of the overture must carry the symbolic and emotional weight of the entire narrative. Prefiguring the schism to come in German music, Wagner’s titular character is torn between the divine, represented by Bach-like chorale writing, and the sensuous, represented by lush chromaticism.

“That’s what I’m here for: to make the character—the inner narrative—of the music potent, and not stop until it’s there,” Elder says. “You have to interest yourself in not only the meaning of the text but also the inner meaning. Music isn’t very good at saying, ‘These are mountains and a storm is coming.’ What music can do, vis-à-vis the Alpine Symphony, is to portray one’s feeling about a storm coming. That’s something wider and deeper.”

An oft-cited example from Heldenleben: the ominous semitone motive spelling out the initials of one of Strauss’ most vicious nemeses, the Viennese music critic Doktor Dehring. The gesture, for two grumbling tubas, is set in parallel fifths—a brazen affront to the conventional rules of harmony Dehring harped upon in his reviews.

Unsurprisingly, critics found the entire tone poem repugnant. Audiences have been kinder: Ein Heldenleben has remained in the symphonic repertoire, mostly uninterrupted, ever since. The very section that a reviewer once decried as “a monstrous act of egotism,” in which Strauss floats snippets from his other tone poems atop one another, is Elder’s favorite.

“He quotes his other works as if he’s hallucinating or half-asleep. It’s as if he’s recalling, ‘Oh, yeah, that was a good one,’” Elder says.

When asked what would be in his Heldenleben—make that Dirigentsleben—Elder is quiet for several seconds, deep in thought.

“Well, the music would have to be full of aspiration, wouldn’t it? Full of energy and positive feelings,” he says. “I would want to put in some expression of love for my family. I’m now a grandfather, and I have a four-and-a-half year old girl who’s wonderful. I would also probably want to express my love and passion for all things Italian. We’ve gone to the same Italian area [Orvieto, 75 miles north of Rome] every summer for 30 years; we rent the same house. It’s miles away from anywhere. I love the food, the wine, the people, the language, the buildings, the paintings and the music. But perhaps there would need to be some sadness, too, because every life, somehow or other, has sadness in it—disappointment, personal tragedies.”

As a brief respite from the teeming, late Romantic worlds of Wagner and Strauss, Elder also leads Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 17 with Pavel Kolesnikov, the Russian-born, London-based pianist with whom Elder has concertized in recent seasons. How does he see that slotting into his very heroic program?

“Not at all,” he says, with a wry smile. “But that’s fine. I don’t want every program to have only one theme. I want the aspiration of Tannhäuser to be contrasted with this formal perfection, this music that made me laugh when I was young.”