Shaw’s Observatory, Holst’s The Planets and a CSO partnership with the Cincinnati Observatory

by Ken Smith

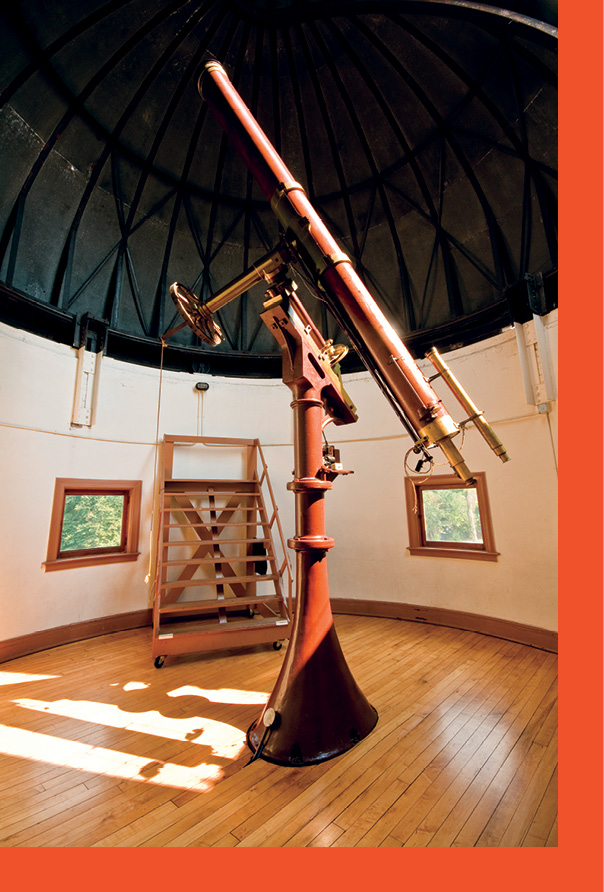

Whatever resources Gustav Holst had at his disposal when he began composing The Planets in 1914, they didn’t include computerized telescopes or astrophotography. If his imagination was sparked by telescopes at all, they were probably more like those of the Cincinnati Observatory, whose 11-inch Merz and Mahler refractor from 1845 is the oldest working telescope in this hemisphere.

On December 2 and 3, when conductor Giancarlo Guerrero leads the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra in a program pairing The Planets with Caroline Shaw’s The Observatory (a CSO co-commission)—with pianist Michelle Cann playing Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody in between—Music Hall audiences will be able to see Jupiter and Saturn for themselves thanks to telescope demonstrations offered by the Cincinnati Observatory, reprising their partnership from the last time The Planets came around in 2015.

“We obviously come in from the scientific side,” says the Observatory’s Executive Director Anna Hehman. “We talk about mass, gravitation. We think of the planets as very static. But here’s this music that gives them personalities. Jupiter is sort of jolly, Uranus is something of a magician. No matter where you come from, you can always think of the planets in a different way.”

Community engagement, whether in public programs at their own historic building or off-site partnerships with organizations like the CSO, has been part of the Observatory’s mission right from the start, when funding for its initial telescope came by collecting $25 donations door-to-door. “Everyone was told right from the beginning, ‘This is not for royalty, or academics. It’s going to be for the people,’” Hehman adds. “It was democracy through astronomy, which is something we’ve always been proud of.”

Cross-disciplinary collaborations have taken on new urgency as institutions try to lure back in-person audiences, but for Hehman the goal is less about expanding separate audience bases as it is about building a larger community. The Cincinnati Symphony wasn’t even the Observatory’s least obvious partner, Hehman admits. That distinction possibly goes to the Red Door Project, a pop-up gallery run by the Art Academy of Cincinnati. “We kind of got the raised eyebrow, ‘You’re doing an art show?’” she says. “But the theme was celestial objects inspired by space, which looked at the romantic side of the skies. The turnout was fantastic, and once people learned about us and were able to see the stars and planets for themselves, it all made sense.”

Students are another target audience. “We have rocket launches, where kids get to design and decorate their own bottle rockets,” Hehman says. “They get to exercise their creativity, which they love. But then we teach them how propulsion works, how weight affects things going through the air. ‘Those fuzzy pom-poms on your rocket are really cute, but do you think they’re really aerodynamic?’ It’s a little sneaky, like hiding vegetables in a smoothie, but it also makes them excited about problem-solving.”

Far from being frivolous play, Hehman adds, the arts have been reentering a dialogue with science in current educational policies. “It used to be all about STEM—science, technology, engineering, math,” she says. “But in the last several years, it evolved into STEAM, putting the arts in there. And lately we have STREAM, to focus on reading and how we absorb information. It’s not just about adding concepts, but changing the way different people connect and learn.”